by Margaret P. Petersen (Edited for continuity by Gary Lee Walker)

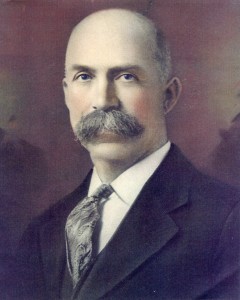

John William Pitcher (or Willie as he was known to his family, this nickname “being shortened to Will in later life), was born June 13, 1871, the second child of John and Rebecca Pitcher, at Smithfield, Utah. He was born within two years after his parents emigrated to Utah.

While an infant, perhaps one year of age, he was severely scalded. Grandma and Aunt Susan, Uncle Ted’s wife, had been given some tea by a friend who had just arrived from England. They made the tea and were anticipating a treat, when Grandma accidentally spilled her tea on the baby she was holding on her lap. Grandma told me how the afternoon was spoiled and the difficulty of treating the burn where the skin had come off with the clothing. To me, this incident seems a foreboding of the many illnesses and accidents which befell him. In my girlhood, I saw him survive several close brushes with death, and such incidents continued to occur. Some say such bad luck is a result of carelessness. To me, he was an example of patience and courage in suffering.

Needless to say, in his childhood he had only the meager necessities of life, but Grandma was resourceful. She was also refined, both by nature and by training in England, and her children were taught to be kind, courteous, and mannerly.

His schooling was very limited, but again it was Grandma who taught him to read, and, with his natural aptness for figuring inherited from his father, he found he fared very well with his contemporaries.

It just occurred to me, I could be writing of Uncle Henry as well as father. With the same home influence, experiences and inherent abilities, their lives ran parallel for many years. However, I have heard Grandma say Uncle Henry was a little more shy than father. But many times she ran out of adjectives in describing their good traits. However, I think father held a little edge over Henry in Grandma’s affection because of the following incident. Father’s two younger brothers died of diptheria, [sic] within a few days of each other. (Father’s life was also despaired of at the time.) By the time Aunt Rose was born, father was eight years of age. When he and Uncle Henry herded cows on the hills, north and west of town, he was eleven years of age. Grandma taught him to care for babies and other household tasks, and he became her depended-upon-helper.

The cows he herded were known as the town herd. They would gather the cows in the morning and return them in the evening. A small fee was charged, but not always collected. Their lunches were scant, but I’ve heard father say they could always catch a cow and fill their cup with milk to drink. They enjoyed the wild fruit when it was in season both for eating and to carry home for drying or preserving.

G-randfather worked on the railroad, the branch line from Cache Jct. around the valley south and up the East side. By the time father was fourteen or fifteen, Grandpa became Section Foreman on the main line of the Union Pacific, on the west side. They resided, at Thatcher, what is now known as Virginia. Just how far his run was I am not sure. But I do know it included Arimo and Downey. Grandma cooked for the section men, and often the train crew ate there. Again, Father was pressed into helping in the kitchen. Edgar, Joseph and Walter were born after they moved to Thatcher.

At seventeen, father was doing a man’s work on the railroad; Uncle Henry had begun working before this time.

Grandma was interested in developing the talents of her children in reciting poetry, singing and music. They had acquired an organ, played the accordion well, and I have never heard anyone get such music out of a mouth organ. Aunt Rose was a natural musician and could play any instrument.

Their social life included house parties, many of which were held at Grandma’s. Father had a few girls, one of whom I wish he had never known, Maggie Fife. Mother always said that was why father called me Maggie (a name I thoroughly detest, and the only thing I could possibly hold against my father). She had her “beau’s” also, because Father teased her about them.

However, each time Father went to Smithfield from Thatcher, he managed to spend most of his time with Mother. Their attraction for each other began in childhood, when their families visited together.

Mother said Father was always different than other boys, never rough or uncouth, and he also did the cutest things. For example, he pulled little radishes from the garden, washed them and gave them to her. He also cracked the hazel nuts for her to eat. Of course, round radishes and hazel nuts remained her favorites.

Father said Mollie had the prettiest eyes and cutest little mouth of any girl he knew. I may, later, write some more amusing incidents of their courtship, as I have heard them often.

They were married on March 23, 1892, by a Justice of the Peace at Smithfield. Mother said that, after being married, they walked down the street and saw Aunt Nancy Pitcher washing, and Father said “How could anyone wash on such a wonderfully special day as this.”

Mother’s wedding dress was a pale pink, cashmere trimmed, with a white silk cord, and basque style. They boarded a train to go to Cannon, now Utida, to Grandma’s for their wedding supper. Grandma Thornley was with them. Mother wore her wedding dress on the train, a breach of good taste which mortified Grandma Pitcher. In telling me of it, Grandma said, “I thought I would drop in my tracks when I saw your Mother get off the train in her wedding dress. Whatever was your Mother thinking of.”

I don’t know what Grandma Thornley was thinking of, because she left her hat on the train, and, when the train pulled out, she excitedly clutched Mother and cried “Aye me Gad, Mary, my hat is on the train.”

They were soon located in a section house in Thatcher where Father had taken over the section and Grandfather had gone down to Cannon. Grandmother Thornley lived with them until just before my birth.

From Thatcher they moved to Camas, Idaho. I believe we were there about three years. Mother cooked for section men as Grandma had done. Besides the section job, Father cared for the windmill, the water tank, and the steam engine that pumped extra water in the tank, when the windmill provided insufficient power. This huge tank held water for the steam engines used on the trains. I remember watching Father climb the windmill to oil it, and also watching the engine run by.

At Camas, the Camas Creek ran past the house. Father was an excellent fisherman and trout could have been a daily fare. He also liked shooting and was a good shot. Ducks, prairie chickens and sage hens varied the diet. I could tell several fish stories that would be difficult to believe in these days of daily limits.

Another memory of Camas was a room called the store room. As purchases were made in case lots, the shelves were stacked with items, much as a regular store. Large pieces of meat came from Idaho Falls. Of course, these large amounts of food were necessary to feed the seven to twelve boarders. Aunt Rose and Aunt Allie helped Father with the work.

By 1900, Father was getting tired and unhappy with his work as Section Foreman. A contributing factor was the type of laborers replacing the local white men. The first replacements were Japanese. They boarded themselves in their bunk house. Father could tolerate the Japanese, then it was rumored that his next crew would be negroes. This was the last straw. Father decided to go back to Smithfield and farm. Mother liked the railroad with the regular hours and income and she never liked farming. Father loved the soil, the animals, and the independent life. Though he was doing what he liked, I agree with Mother, the remuneration was not equal or commensurate with the hard work of father and mother or of the family.

While at Camas, Father purchased one-hundred twenty acres of land for $4.00 per acre, through a government land act, the name of which has slipped my mind. William Goodwin helped make the selection. It was located in the flats just below the west hills in Cornish. Many have wondered about the selection but, at the time, the clay soil yielded better. The land was covered with a heavy growth of sage brush. The land was cleared of the sage by first, plowing and then, using a grub axe. Father would spend his summers in Cornish planting the cleared land and clearing more sage each summer until it was finally all under cultivation. He also farmed Mother’s twenty in Smithfield. Mother stayed in Smithfield and milked the cows, cared for the chickens, the pigs, and the garden, which included irrigation in the summer. Of course, we children helped out. Mine was mostly baby-tending, until Cyril and I were old enough to take over the milking, etc.

Every spare dollar went into building the West Cache Canal. Each spring, Father would sell a team of young horses. Cows were sold and other badly needed funds went into the canal. Stock in the canal was given for the contributions. A dream was realized when the waters flowed the length of the ditch. Many costly breaks occurred, however, which called for more money and labor. The canal was built with horsedrawn, hand-operated scrapers. But, with the coming of power equipment, former difficulties were overcome. A memorial should be built honoring the men who sacrificed so much, many of them losing their farms, that water could be poured on the dry and parched ground, and the soil made to yield in abundance. The present generation is surely reaping benefits from the efforts of their parents and grandparents. It would be difficult to picture the west side of the valley, with its sage brush and deep sand, while it was in this arid condition.

In the spring of 1906, Father persuaded Mother to sell her inheritance. This she did, and received one hundred dollars per acre, an unheard of price up to that time. With five hundred dollars from the sale of the city lot and log home, Father was able to buy another 120 acres of land with a three room rock home on it.

Mother was sad and used to stand by the fence and look towards Smithfield and cry. I knew she cried because I could see her pick up her apron and wipe her eyes. Father used to comfort her and tell her he would take her back to Smithfield to live in ten years. Of course, this promise was made in good faith, but circumstances did not permit it. Mother’s attitude must have changed, because in 1912, one year after my marriage, they built a large home, a nine room giant, which housed a growing family of children and grandchildren, and had room for many parties and gatherings of relatives and friends. A large dining room and a well stocked pantry always made it possible to set an extra place or two. It was not unusual to see the pantry shelves laden with twelve to twenty pies. Father was always a good provider. The farm produced milk, eggs, chickens, and meat. The smoke house always held cured hams, bacon and shoulders for summer eating. Mother cared for the cows and the chickens.

Each one of the family worked, doing their share according to their age. Laziness was the cardinal sin. Phoebe and Mozell herded cows and pigs when they were small. Later, I think the next three boys may have taken over the herding. The last of the family had life much easier because there wasn’t a new baby coming along every other year to be cared for. There were also a few more conveniences.

After moving to Cornish, Father spent several years as Assistant Superintendant and Superintendant of the Sunday School and as a Ward Teacher. In 1917, he sent my brother, Cyril, on a mission to the Western States. In November of 1920, Father left for a mission to England,

leaving Mother and seven children at home. To me, an invaluable lesson in faith and yielding obedience to any call made by those in authority was learned.

Mother worked in the Relief Society as Treasurer and visiting teacher for many years. Her large family prevented her from participating as much as she was capable of doing.

Their marriage was solemnized in the Logan Temple, in March of 1896. The same day, Grandma and Grandpa Pitcher, Aunt Ellen and her husband received their endowments.

Twelve children were born to this union in the following order: Margaret, Cyril, and Harvey at Smithfield; Phoebe at Camas; Mozell, Decon and Brown at Smithfield; Melvin, Bessie, Vaudice, Valden and Bertha at Cornish.

Father was a kind, tender-hearted, sympathetic and wise parent. Because he was near the eldest and mother the youngest in the family, he had more experience caring for children than she. Mother was always willing and glad to do the housework, but she turned to Father to diagnose and to advise in the treatment of any ailments. He was a good disciplinarian and expected obedience, which he received without argument. He was a good neighbor and a good citizen, never shirking a duty or responsibility.

He loved flowers, and it was a family sight to see him come in with a bouquet of flowers he had gathered on his walks around the farm. Wild roses, lilies and pinks were his favorites. He cherished the hopes that he could retire to a small home, and to gardening, so he could devote his time to growing the beautiful flowers he loved.

He loved sports, and delighted to play games with his children and grandchildren, which he did to the last. He enjoyed the great outdoors. Yellowstone Park trips, and days spent in the canyon, with outdoor cooking and eating, were always a treat to him.

He continued working hard. The depression of the thirties made it more difficult to make the farming pay, and caused him much anxiety and many sleepless nights. The combination of work and worry proved too much for his poor heart. He made a brave effort to recover but succumbed on December 16, 1938, several days after suffering a heart attack, surrounded by his family, who owed him so much.

I am attaching a copy of a poem written by Josephine Jackson, a granddaughter, which I believe tells more than the foregoing that I have written.

THE HOUSE ON THE HILL

by Josephine P. Jackson

There’s a house that stands on the brow of the hill,

Molly once lived there with a man named Will.

And like a spider weaves its web so secure,

There are memories clinging to every door.

There were geraniums blooming on each window sill,

They whispered the story of Molly and Will.

Will was fragile of body, but mighty of mind

There were few men around with heart so kind,

And he did not weary of good deeds to do,

His friends were many and his enemies few.

And Molly always stood by his side,

She performed household duties, with joy and with pride,

And she did not tire of the many tasks that she had,

They seemed sorta light, if they made Will feel glad.

They reared twelve children and thus they did fill,

With happiness and love, that House on the Hill.

But it wasn’t so long until they were alone,

The children had gone to make homes of their own.

Then the Grandchildren were welcomed with open arms,

They flocked to the House with all of its charm.

Twas here the doors were always opened wide

It was like being in a Palace, once you were inside.

When Thanksgiving and Christmas arrived with its holly

The tables were spread by “Grandmother Molly.”

There was not one room in that house too small

No matter the number, there was room for all.

And “Grandfather Will” was right there too,

To clasp each hand and to ask “How are you?”.

Whatev’r the occasion, he was always the same,

He joined in the fun and played every game.

And then alas, there came that day

When Will decided to go away.

And Molly was lonely, when he was gone

But did her best to carry on.

Then came the great grandchildren and she would say, “I’ll be blest,

Each one that comes, tops all the rest.”

Then the Grandson’s were taken away to war

They were shipped abroad to the lands afar,

But Molly was thoughtful and made them feel better

It lifted their morale to receive Molly’s letter

One day Molly was tired and she went away too,

She went to find Will as she knew she would do,

And tho they are gone, We are sure they do still

Maintain a “House that stands High on a Hill.”

(A short sketch of Mother’s life, which I wrote when she was honored by the Relief Society in 1940. Margaret P. Petersen)

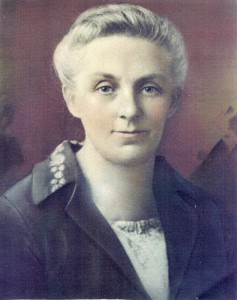

Mary Clarissa Thornley, daughter of John and Margaret Stringfellow Thornley, was born April 27, 1873, the youngest of seven children. Mother grew up like most of the pioneer children, enjoying the simple entertainment of the day. For several reasons, her education was received at the Presbyterian School. First, the school was located near their home. Second, there was no tuition to pay. Third, the instructors, who come from the east, were better qualified to teach than most pioneer teachers and the pupils received a very good foundation in elementary education. Mother was an apt scholar and received many rewards, such as pictures and small books, for her aptness and behavior.

At thirteen, a great sorrow came into her life. Her kind and indulgent father was taken away, leaving his wife in a state of semi-invalidism. Before his passing, he called little Mary to him and asked her to promise to always be kind and thoughtful to her mother. He was followed in death by two grown sons. To comfort and wait upon an ailing and grief stricken mother was a great responsibility for a young girl, but, though she had to give up her schooling and forego many parties and youthful pleasures, she remained faithful to her promise. And today any conversation with her girlhood friends will include such remarks as “My but Molly was surely good to her Mother,” or “Molly always considered her Mother before herself in everything.”

This devotion was rewarded by her gaining the love of a childhood sweetheart who admired and loved her for her kindness. At nineteen, she was married to John William Pitcher, who proceeded to make up to her any pleasures she had been denied. You may wonder how Mother could think of marrying, but grandmother encouraged it, for she recognized in the young man the same qualities that her own husband had possessed.

Mother often said that her mother did the courting. As she was unable to work, she could dress up and receive and entertain father while mother was doing the evening work. Then, when they were married, she took her mother to live with her at Thatcher (later, Virginia), Idaho.

This marriage was a very happy one. Their early married life was spent working on the railroad. Mother cooked for railroad men much of the time. Work was not always permanent and sometimes money was scarce, but mother never cared as long as father was near.

As their children grew older, they decided they must establish a permanent residence to provide them an opportunity to attend school.

In 1900, they settled in Smithfield, Utah, where they resided until the spring of 1906 when they moved to Cornish. Mother was persuaded against her will, but father promised her they would return to Smithfield in ten years. But it has been thirty-four years since then, and she has lost all desire to leave. Births, marriages, hard work and death has made Cornish home to her.

Mother was privileged to rear twelve children to maturity. When asked how they knew they could provide for so many, she said, “They never thought about that in those days.

Her self sacrificing nature has always been in evidence. She stayed in the background, endeavoring to make it easier for members of her family to do their part. She willingly sent her husband and two sons into the mission field and still encourages each to do what is asked of him.

Their home has always been a gathering place for friends and relatives. Everyone knew they would receive a royal welcome. Also, they were sure of a good dinner. Each of her grandchildren longed to go to Grandma’s, and wondered how it was she always had something good to eat.

Mother is here today insisting that she doesn’t deserve this honor, but “we who know her best – love her most, and know that she is most deserving.”

(the remainder was written later, to end the story)

For two years after father’s death, mother lived in the old home. She saw Bertha and Valden marry. Her health was broken and it was too much for her to keep up a large home.

After Valden’s marriage, she lived alternately with her daughters Margaret, Bessie, and Vaudice, and with Valden and Doris in their new homes. Her health was alternately fair and poor but, through it all, she maintained the will to live, especially when thirteen of her grandsons were in World War II. She wished to live and see them all return. She was always kind and thoughtful and her grandchildren and great grandchildren were a constant delight to her.

Her death in October of 1946 was caused by a cerebral hemorrhage, suffered three days previously. Her twelve children surrounded her bed knowing that she was going to meet her beloved Willie.

3 comments

Hi, I have a very old crossstitch work signed Mary Thornleys work 1828. (in crosstitch). It’s about 14″x14″ and the edges are tattered. It is so lovely and I decided to see if I could google some history that would identify this Mary Thornley. Could this possibly be her?

I have a crosstitch piece signed Mary Thornleys work 1828 (in crosstitch). It iss old and frayed on the edges but still lovely. Just wondered if it might belong to your Mary Thornley???

Author

I don’t think so as my ancestor was born in 1873.